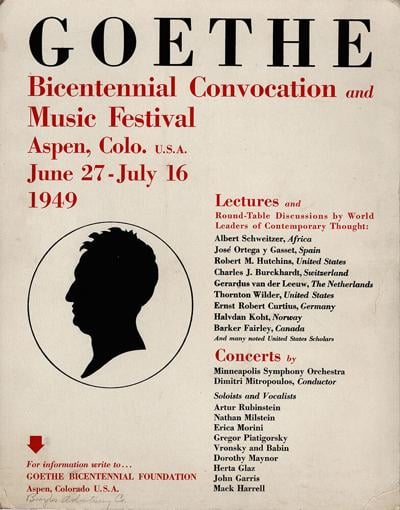

Editor’s note: This story is the first of a four-part Aspen Journalism series detailing Dr. Albert Schweitzer’s 1949 visit to Aspen to keynote the Goethe Bicentennial convocation, and examining the legacy of Schweitzer’s ideals for the Aspen community. The series will continue through Thursday in the Aspen Daily News.

The high ideals of Dr. Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) represent the greatest challenge and opportunity Aspen has ever faced.

“A man is truly ethical,” wrote Schweitzer, “only when he obeys the compulsion to help all life which he is able to assist, and shrinks from injuring anything that lives. Life as such is sacred to him. He tears no leaf from a tree, plucks no flower, and takes care to crush no insect.”

A new and growing movement launched in September by a handful of community thought leaders is seeking to revive the foundational values of Aspen. They are reaching back 75 years to the lofty moral tone that Albert Schweitzer brought here when he honored another moralistic avatar: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

With Schweitzer and Goethe as exemplars, Aspen made a tectonic shift from silver mining to an idealistic culture with utopian overtones. This set up Aspen for success while consigning it to a post-utopian era of super-gentrification.

“The two basic ideals of a profoundly human attitude are purity and kindness,” Schweitzer said in July 1949, speaking French at the lectern in the Eero Saarinentent at the Aspen Meadows. “Purity frees man from hypocrisy, and kindness is the supreme manifestation of the spirit in man. Goethe’s principle is: ‘Do good for the pure love of the good.’ By this individual practice of good on the part of a great number, the well-being of society is realized.”

Service to humanity was the underlying message of these messianic Germanic giants whose combined grace reflects today on the outpouring of humanistic endeavors in Aspen and the Roaring Fork Valley, where more than 300 nonprofit organizations strive to contribute to human well-being. Such beneficence reflects Schweitzer’s mantra “Reverence for life,” a personal philosophy he discovered through an epiphany on a river in Africa almost 100 years ago.

“‘Reverence for life’ is already here in Aspen today and within every single person up and down the valley,” said Schweitzer scholar Dr. Lachlan Forrow in a September talk at the Aspen Chapel, titled “Reverence for Life and Aspen Today,” that fomented the Schweitzer revival.

A Princeton philosophy major, Harvard Medical School graduate and board member of the Albert Schweitzer Fellowship, Forrow unconditionally linked Schweitzer with today’s Aspen. “All we need to do is recognize that, and then — as with any living thing, whether just a tiny seed or seedling, or already something more — nurture it within ourselves and in others, and it will grow, blossom and bear ever-increasing fruits.”

Schweitzer’s missionary presence is experiencing a resurgence in Aspen today as a healing salve for rifts within the Aspen community. As grandiose displays of material wealth abound here, a communal essence has been eroded. Without acknowledging and reflecting upon the founding ideals of Aspen’s cultural renaissance in 1949, opulence is mere dross, and many feel that Aspen has become a glossy backdrop to the religion of materialism, something that would have been anathema to Schweitzer, Goethe and the conveners of 1949 Aspen.

The effort to restore Schweitzer’s ethic reflects the desire for something much deeper and more lasting that may once again ennoble Aspen by restoring higher values than a sprawl of mountain mansions, a fleet of private jets, serial home ownership and the measure of wealth by astronomical real estate prices that have driven out the workforce and compromised community values.

“Albert Schweitzer was the rock star of his day,” said Greg Poschman, a Pitkin County commissioner who is helping to spearhead the Schweitzer revival. “We need to find someone who is heir to that legacy and can keep it going.”

“If we can have at least one day a year for a Schweitzer memory day,” said Gregg Anderson, a former Aspen Chapel minister, “and maybe a Schweitzer award for humanitarian virtues, that would be a meaningful outcome.”

“Sacrificing what’s better for me over what’s better for the greater good, that’s really the idea that Albert Schweitzer brought to Aspen,” said J.R. Atkins, minister at the Aspen Community Church. “This is about how Aspen is going to set a model for the rest of the world.”

“One of the things Schweitzer stood for was a sense of community,” said former Aspen Mayor Bill Stirling. “A Schweitzer event next summer would be a start to something meaningful, especially when our community is rent asunder. I accept the evolution of communities; they don’t stay the same. But Schweitzer’s life could have a profound effect on rebuilding community in Aspen, thanks to his temperament and devotion, and to being the kind of person he was.”

Restoring Schweitzer to significance in Aspen comes at a time when the materialism he saw as a distraction to ethics and morality is more rampant than ever, when celebrity status is bestowed on popular media icons and power-driven billionaires, when community is fractured and environmental issues imperil nature herself.

“What Schweitzer did,” Forrow told the community at his Aspen Chapel talk in September, “was identify and name your capacity for reverence for life, and then encourage people to realize that when we cultivate that in ourselves and in others, and then it steadily blossoms and grows ever-deeper roots, we can have the kind of world that we all yearn for.

“My hope,” he concluded, “is that this will include events in Aspen in summer 2025, from which Dr. Schweitzer’s legacy can continue to grow in ways that are of value to a wide range of individuals and communities.”

And so emanates an echo from Aspen’s hallowed past.

Schweitzer scholar and physician Lachlan Forrow and Rwandan educator Manzi Kayihura pose at the Schweitzer bust in Aspen’s Paepcke Park in July 2024. Kayihura was here to collaborate with the Aspen Center for Environmental Studies, and Forrow spurred a local Schweitzer movement with an Aspen Chapel talk he gave in September.

Courtesy of Lachlan Forrow

When Schweitzer set foot in Aspen in 1949, he was on a mission to restore the ethic of humanism that had suffered nearly irreparable damage during World War II, the Holocaust and the nuclear carnage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. The world was adrift with a broken moral compass, and Schweitzer was seen as an enlightened navigator who could steer humanity toward more promising shores.

He appeared in Aspen dressed “in the fashion of 50 years ago,” as he was later described, with an unruly thatch of gray hair and a walrus mustache. Humble, self-effacing and yet radiant with idealism, Schweitzer personified the highest of humanistic ideals through selfless service. Simply being in his presence could move one toward new heights, whether he performed a Bach organ piece, sermonized on the historic Jesus or applied his medical skills to the underserved.

Schweitzer’s divine presence was cloaked in a humble guise because he eschewed the fame that brought him here. During a standing ovation after his keynote address in the Music Tent that sanctified day in July, his head was bowed as if he were withstanding a cold rain. The lofty sobriquet bestowed upon him — “The Living Saint” — was a kind of embarrassment to this moralistic servant.

The story is told that Schweitzer, traveling once by train in Europe, arrived at his destination and, to the surprise of the host who was there to meet him, stepped out of a third-class coach. “Why did you take third class?!” asked his astonished patron. Schweitzer replied: “Because there was no fourth class.”

Schweitzer’s invitation to Aspen in 1949 originated from the University of Chicago with a pledge of more than $6,000 to support a leprosy clinic that Schweitzer planned to build at his bush hospital in Gabon, a nation on the Atlantic coast of central Africa. The event was a celebration of the 200th birthday of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and the venue would be Aspen — this at the behest of Chicago industrialist Walter Paepcke and his wife, Elizabeth, who were already invested here, materially and spiritually.

The originator of the convocation was Giuseppe Antonio Borgese, a philosophy professor at the University of Chicago. He convinced Robert Maynard Hutchins, the university’s chancellor, that the world needed an infusion of Goethe’s spirit in order to repair the shattered, post-industrial World War II cultural landscape and to reinvest a sense of nobility with the German people, something that ultimately appealed to Paepcke, who was of German descent.

“The intent” that Borgese stated in his speech at the Goethe festival in Aspen was “helping some lagging yet not quite obdurate hearts to realize that the permanent ambassador of the German community to the community of man is Goethe, not Hitler.”

With this prodding, Hutchins approached Paepcke, whose friendship he had nurtured through the Great Books program in Chicago. Together, they conspired to channel Goethe’s spirit in Aspen, with Schweitzer’s agency. Paepcke explained in the foreword to “Goethe and the Modern Age” why Aspen was chosen over Chicago: “It was desirable to have as a site a small, peaceful, simple, and somewhat remote community free from the distractions of a large city, to which people would have to make a pilgrimage because they wanted to be there.”

It took a lot of coaxing and a little cunning to persuade Schweitzer to make his one and only visit to the United States to facilitate Paepcke’s vision. The contribution pledged to his bush hospital in Africa was Schweitzer’s compensation for bringing Goethe to Aspen through a studied interpretation of Goethe’s life, his works and his witnessing during his lifetime (1749-1832) to the perils of the Industrial Revolution. Just as the “Aspen Idea” later defined the “whole man,” so Schweitzer and others defined the whole Goethe during the three-week celebration of lectures, music, discourse and communion. Schweitzer’s focus on spirit framed his esoteric view of life.

“The fundamental idea, which is of the utmost import,” Schweitzer told a reverent Aspen audience, “is that in nature there is matter and spirit, the two together. We find that in us also there is matter and spirit. Searching into the phenomena of the spirit in us, we realize that we belong to the world of spirit and that we must let ourselves be guided by it. The whole philosophy of Goethe consists in the observation of material and spiritual phenomena outside and within ourselves.”

Schweitzer’s Aspen travelogue reveals a series of encounters and personal discoveries that landed him here with eyes wide open on his sole visit to America. The following summary was gathered from his writings and from newspaper and magazine accounts.

Tuesday, June 28, 1949 — Arrival in New York City: Schweitzer had refused previous invitations to come to America, largely because, his friends said, of what he had heard about U.S. publicity and “ballyhoo methods.” When his ship, the Holland America liner Nieuw Amsterdam, docked in Hoboken, New Jersey, he got his first taste of it. When he and wife, Helene, debarked, they were met by more than 40 photographers and as many reporters.

Reporters wanted to know how he could renounce civilization and sacrifice his life in the jungle. “It is not renouncing anything,” Schweitzer said, a twinkle in his eyes. “When you are doing some good, you are not making a sacrifice.”

Wednesday, June 29, 1949 — New York City: During a four-day stay in New York City, Schweitzer’s celebrity caused him later to note: “When all those reporters were let loose on me, I felt like a virgin thrown to the lions in the arena. In the apartment where I was staying, one day a piano tuner came in and, when he thought I was not looking, he was taking photographs.”

Friday, July 1-3, 1949 — New York City to Chicago: When Schweitzer boarded a train from New York to Denver, he began a 50-hour journey. He wrote a brief description of the first leg of his journey in a letter to a longtime friend: “For the past hour we’ve been traveling through a plain filled with grain. Nothing but isolated farms. The houses look strangely small. We’ll be in Chicago in another three hours, with a one-hour stopover. I believe I did the right thing in agreeing to give this speech and coming to America.”

Sunday, July 3, 1949 — Chicago to Denver: Letters of invitation that Schweitzer had received from University of Chicago Chancellor Robert Maynard Hutchins bore a Chicago postmark and led the good doctor to assume that Aspen was a suburb of the Windy City. Still, he evidently took it well when he and his wife, Helene, both elderly, were informed that they must travel an additional 1,000 miles west to a decrepit mining town at 8,000 feet in the Colorado Rockies.

After the Chicago stopover, he would write in another letter: “For 10 hours now we have been rolling at sixty-five miles an hour, crossing an immense plain in wonderful weather. It is enchanting.”

As Schweitzer watched the Great Plains roll by, he was told the story of an airlift that had carried food to snowbound animals the preceding winter. “Ah,” he said, “what a magnificent feat! Vive l’Amerique!” Later, in Europe, Schweitzer remarked that he believed there was more reverence for life in America than anywhere else in the world.

Monday, July 4, 1949 — Arrival in Aspen: When the celebrated and exhausted guests finally reached Denver, on July 4, 1949, their train was detoured because of a rockslide on the Denver and Rio Grande route. On that final leg of this epic trip, a woman came up to Schweitzer on the halted train and said: “Oh, Dr. Einstein, I am so interested in your book. I have it with me, your book on relativity. Would you mind inscribing it for me?” Schweitzer, taking the book with generous humor, flourished the following signature on the fly-leaf: “Albert Einstein, by his good friend Albert Schweitzer.”

Arriving in Aspen by car, Schweitzer was said to remark: “Aspen ist zu nach an den Himmel gabaut.” (“Aspen is built too close to heaven.”) Worried that the gates of St. Peter would open and take him here, Schweitzer stoically endured the altitude to manifest one of the loftiest presences Aspen has ever known. Perhaps the only thing that compares was the visit of the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, in 2008 for a three-day event celebrating Tibetan art and culture.

Elizabeth Paepcke, whose droll sense of humor made her a wonderful storyteller, took up the tale of the Schweitzers’ arrival in Aspen decades later in an Aspen Institute speech:

“The festival had started, we were all exhausted — lectures all day, concerts at night, suppers afterward for hungry musicians, and to bed at 2 a.m. The Schweitzers were late in arriving. My husband, late at night, led them to their beds in our guest cottage, the former stable of Pioneer Park. [Afterwards, it was said the Paepckes had bedded a saint in their manger.]

“I was asleep and did not know that the Schweitzers had been told that breakfast was at 8 o’clock sharp. At 7:45 the next morning, the house was awakened to a spine-chilling yell, which made me leap from my bed and my sleep. In the bathroom, Walter Paepcke stood, very red and very naked, in 6 inches of water — water which was bubbling up from the drain of the shower bath, spilling out of the wash stand and toilet bowl and rapidly filling the tub. ‘Don’t stand there! Do something!’

“As I was, nylon nightgown, wild hair, bare feet, and what was worse, that mark of vanity on my forehead — a square of court-plaster called a ‘frownie’ — I darted out of the room, by the front door, through the living room to the kitchen, where I seized mop, bucket and sponge. I gave the horrified maids orders to find and turn off the plumbing connections, and then streaked back the way I had come.

“At that moment, our Victorian clock chimed 8 a.m. The front door opened. There stood the great man himself, just as he had been described to me: shaggy mane of gray hair, amused brown eyes, immense drooping mustache, thin black folded tie, old-fashioned long coat — and on his arm an elderly lady in gray and garnets who looked like a pale moth.

“I stared at the doctor. ’Oh,’ I cried, ‘our plumbing has backed up, there is water all over the floor, and I have to rescue my husband from the bathroom!’

“‘I see,’ said Dr. Schweitzer slowly, as he looked me over from tousled hair to bare feet and mop. ‘I see,’ he repeated, ‘Mrs. Schweitzer and I are just in time to witness the second flood (die zweite Weltflut).’”

Editor’s note: This series is being produced through the Aspen Daily News’ ongoing collaboration with Aspen Journalism. Part 2 will continue on Tuesday with Albert Schweitzer’s visit to Aspen beginning at the Paepcke home, then to the Music Tent with the good doctor’s keynote address, followed by his epiphany of a unified philosophy based on reverence for life.